What do post-modern approaches have in common?

The term “post-modernity”doesn’t signify an era that follows modernity, but a frame of mind that’s critical of the assumptions of modernity. It’s a predominantly academic movement that has challenged most received ways of doing history, notably in the following ways:

- Instead of using historical sources to investigate the past, it rejects the idea that texts connect us in knowable ways to realities outside the texts.

- It doesn’t construct narratives, which it regards as a kind of fiction. It claims that when historians think they have discovered a past, they have really only constructed it.

- Instead of trying to minimize the historian’s bias, post-modern historiography acknowledges it. All historians are ‘situated’ in ways that determine and relativize their perspective.

- It rejects grand generalized themes in history, not least “progress”. The past doesn’t have a coherence of its own.

- It understands social identities, such as race, ethnicity, and gender, as socially constructed. To suppose that these identities are stable and cross-cultural is “essentialist” thinking.

- Indeed, personal identity itself is an ever-changing construction, which problematizes discourse about human subjects.

- Instead of affirming truths about the past, it deconstructs and dismantles narratives about the past. To do so, it claims, is a positive service, since history has usually been used to justify a network of relationships of power.

A stepping-stone towards post-modernity: Thomas Kuhn

Kuhn, a philosopher of science who taught at the University of California at Berkeley, at Princeton, and at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, disputed the idea that science progresses by accumulating facts  and testing hypotheses. In The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (1962) he argued that science works by fitting theories and facts into pre-existing interpretive paradigms. (Thus the Ptolemaic astronomical system, which placed the earth at the centre of the universe, withstood counter-evidence by inventing a corollary system of complex cycles and epicycles that could explain it.) At some point, though, anomalous evidence puts such a strain on the coherence of the paradigm that a shift in paradigm is required. Then scientists will begin fitting their evidence into the new paradigm, until another shift is required.

and testing hypotheses. In The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (1962) he argued that science works by fitting theories and facts into pre-existing interpretive paradigms. (Thus the Ptolemaic astronomical system, which placed the earth at the centre of the universe, withstood counter-evidence by inventing a corollary system of complex cycles and epicycles that could explain it.) At some point, though, anomalous evidence puts such a strain on the coherence of the paradigm that a shift in paradigm is required. Then scientists will begin fitting their evidence into the new paradigm, until another shift is required.

Kuhn’s thesis has been much critiqued, but not vanquished. A recent illustration of its use is the question whether the discovery of dark energy in 1998 can be fit into the century-old “Standard Cosmology” of theoretical physics, or will require a new paradigm.

Kuhn himself wasn't a post-modern relativist, but his idea of the paradigm shift prepared some historians to think that historical sources don’t straightforwardly get us to the objective truth about the past after all. If historians are like scientists, they may be working out of received paradigms that they have failed to critique. Kuhn’s theory has been invoked, for example, by feminist historians of Christianity, such as Elizabeth Clark and Merry Wiesner-Hanks, who wonder if evidence for the influence and agency of women in the Christian past will shatter top-down, male-dominated paradigms of historical change. They suggest, though, that what keeps the existing paradigm in place is not its ability to maintain coherence, but the politics of a male-dominated academia.

Some examples of post-modern approaches to the history of Christianity

HAYDEN WHITE, METAHISTORY (1973)

White, who taught at the University of California at Santa Cruz and at Stanford University, argued inMetahistorythat  historical writing is shaped by language rather than by evidence. Language, he said, isn’t a neutral medium for representing the past. It determines what can be said. Even the syntax of a single simple English sentence, with a subject, verb, and object, requires historians to write about the world as a place where subjects cause things to happen to objects. In reality, subjects and objects aren’t so tidily differentiated, and their relationship is usually far more complex and subtle than a sentence can show. And when we move beyond simple sentences to entire discourses, our language imposes still greater restrictions. Thus when historians give narrative accounts of the past, they are required to make use of available emplotment devices. In White’s view, there are exactly four archetypal plot structures from which historians have to choose, even before they begin writing. So where traditional historians have supposed that they have marshaled logic and evidence to their construction of the past, they have really relied on their rhetorical skill to make a persuasive case.

historical writing is shaped by language rather than by evidence. Language, he said, isn’t a neutral medium for representing the past. It determines what can be said. Even the syntax of a single simple English sentence, with a subject, verb, and object, requires historians to write about the world as a place where subjects cause things to happen to objects. In reality, subjects and objects aren’t so tidily differentiated, and their relationship is usually far more complex and subtle than a sentence can show. And when we move beyond simple sentences to entire discourses, our language imposes still greater restrictions. Thus when historians give narrative accounts of the past, they are required to make use of available emplotment devices. In White’s view, there are exactly four archetypal plot structures from which historians have to choose, even before they begin writing. So where traditional historians have supposed that they have marshaled logic and evidence to their construction of the past, they have really relied on their rhetorical skill to make a persuasive case.

How a historian uses rhetoric to load an argument

In the historiography of Christianity, a great example of the use of rhetoric to pack a historical argument is given by Maurice Wiles in The Making of Christian Doctrine. Speaking of a nineteenth-century work on the history of the fourth-century heresy known as Arianism, Wiles writes, “Arian doctrine has been described by Gwatkin as ‘a mass of presumptuous theorizing, supported by alternate scraps of obsolete traditionalism and uncritical text-mongering,’ which is another way of saying that it is based on reason, tradition, and Scripture and that Gwatkin does not approve of it.”

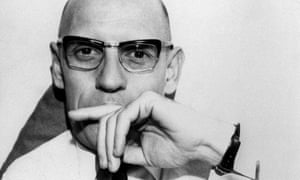

MICHEL FOUCAULT

Foucault, a philosopher and historian who taught at the Collège de France and had several visiting  academic appointments elsewhere, reacted against the Annalistes who looked to persistent structures in the longue durée for the most secure ground of history. Instead, he preferred to study independent and very limited realities, most especially discourses. These weren’t to be studied for what they signified about realities outside themselves, but simply for the distinct rules of discourse that they revealed. In his historical work, Foucault analyzed individual for their internal self-contradictions, the ruptures and discontinuities that they revealed when historians read them ‘against the grain’. He rejected the traditional approach to history that aggregates texts as pieces of evidence towards generalized all-encompassing concepts.

academic appointments elsewhere, reacted against the Annalistes who looked to persistent structures in the longue durée for the most secure ground of history. Instead, he preferred to study independent and very limited realities, most especially discourses. These weren’t to be studied for what they signified about realities outside themselves, but simply for the distinct rules of discourse that they revealed. In his historical work, Foucault analyzed individual for their internal self-contradictions, the ruptures and discontinuities that they revealed when historians read them ‘against the grain’. He rejected the traditional approach to history that aggregates texts as pieces of evidence towards generalized all-encompassing concepts.

Foucault and the history of Christianity

Mark Jordan of Harvard Divinity School, and a Reynolds lecturer at the Toronto School of Theology in 2013, suggests that Foucault thought of the history of Christianity not as a story of people and events, but as a library of genres. Foucault had no interest in correcting Christian narratives, but he loved reading Christian texts as examples of speech with power.

THE "LINGUISTIC TURN"

White and Foucault initiated the post-modern “linguistic turn,” which focuses on the language of texts rather than their function as evidence for realities outside themselves. In this approach, when historians read texts, they have no way of distinguishing the author’s experience of the world from the author’s way of expressing things. So discourses can’t reliably connect us with wie es eigengtlich gewesen, but with meanings. These meanings, however, can’t be expressed as propositions. They’re too fluid and elusive to be objectified.

How the linguistic turn can be applied to the history of Christianity

According to Elizabeth Clark, a senior historian of Christianity who is attracted to “the linguistic turn,” many of those in the area of early Christian studies have already moved in the direction of focusing on textuality. Early Christian literature is particularly appropriate for this approach, since it’s intentionally rhetorical and highly ideological. She gives examples of what historians of early Christianity can do: Eusebiu s can be read not for his account of ‘what really happened’ in the early Church, but for how his history of the Church “shores up claims for the dominance of the proto-orthodox Church, enhances its leaders’ prestige, and justifies particular institutions and teachings."

s can be read not for his account of ‘what really happened’ in the early Church, but for how his history of the Church “shores up claims for the dominance of the proto-orthodox Church, enhances its leaders’ prestige, and justifies particular institutions and teachings."

Lives of martyrs, as Averil Cameron (pictured here) has argued, can be studied not with the purpose of looking for kernels of historical truth underlying the embellishments, but for the way they “embrace all subjects — male, female, high, low — and all literary levels.” Clark thinks one reason saints’ lives were so popular was that they disclaimed the elitist pretensions of classical historiography, and democratized the understanding of Christian history.

Augustine’s representation of his mother Monica in the Confessions and the Cassiciacum  dialogues, whether or not it’s “historically accurate” in the Rankean sense, points to his theology of gender. It’s notable that Augustine portrays Monica, who was presumably illiterate and uneducated, as wiser than her famous son in some of her remarkable philosophical insights, and more inspired in her piety. Monica arguably functions for Augustine as a representative of the unnumbered Christian laypeople who can attain to wisdom without the elite male privilege of formal education.

dialogues, whether or not it’s “historically accurate” in the Rankean sense, points to his theology of gender. It’s notable that Augustine portrays Monica, who was presumably illiterate and uneducated, as wiser than her famous son in some of her remarkable philosophical insights, and more inspired in her piety. Monica arguably functions for Augustine as a representative of the unnumbered Christian laypeople who can attain to wisdom without the elite male privilege of formal education.

This icon of St. Monica was written by reinkat.

GENDER STUDIES

Gender studies emerged in the 1980s as a post-modern challenge to women’s history. Gender historians regarded gender as a social construct, adaptable and malleable. They suspected women’s historians as essentializing gender, as if there was such a thing as a common women’s experience across cultural and historical boundaries. Gender historians also criticized women’s history for falling into a rut of representing the history of women as a history of victimization and marginalization. Women’s historians, for their part, complained that gender historians weren’t willing to talk about women unless men were also brought into the picture, which seemed to them a step backwards. In some places gender history has supplanted women’s history; in some places they co-exist, or overlap.

Gender studies in Christian historiography in Canada

An example of a gender approach in the history of Canadian Christianity is Marguerite Van Die, “Revisiting ‘Separate Spheres’”: Women, Religion, and Family in Mid-Victorian Brantfod, Ontario,” in Nancy Christie, ed., Housseholds of Faith: Family, Gender, and Community in Canada, 1760–1969 (McGill–Queen’s, 2002): 234–263, which challenges the premise that by default women occupied a domestic sphere, men a public sphere. Gender roles, she argues, were far more adaptive in reality.

An example of a gender approach in the history of Canadian Christianity is Marguerite Van Die, “Revisiting ‘Separate Spheres’”: Women, Religion, and Family in Mid-Victorian Brantfod, Ontario,” in Nancy Christie, ed., Housseholds of Faith: Family, Gender, and Community in Canada, 1760–1969 (McGill–Queen’s, 2002): 234–263, which challenges the premise that by default women occupied a domestic sphere, men a public sphere. Gender roles, she argues, were far more adaptive in reality.

POST-COLONIAL APPROACHES

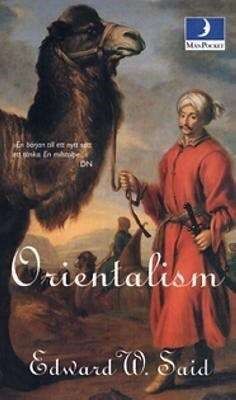

As with our other labels, “post-colonial” can mean many things. I’ve classified it here as post-modern since it can mean a critical way of reading imperialist discourse. (It can also mean, for instance, a study of how groups change as they move from colonization to independence; that can be done in a “modern” approach.) Like the term post-modern, which doesn’t imply that modernity is gone, the term post-colonial doesn’t imply that imperialist relationships have disappeared. It simply means that colonialism is to be critiqued.

Post-colonial approaches are commonly traced to Edward Said’s Orientalism (1978), which showed that, historically, when western discourse spoke of the East (the “Orient”), it had no external referent. It was simply a construct of a discourse, representing what was “the other” as compared to Western ways of doing and thinking. To speak of the “East” was a way of validating the superiority of the West, and therefore justifying the colonization of eastern peoples.

Unlike imperial history, which studies imperial leaders, their administrations, and their policies, post-colonial approaches seek to understand the experience of subjugated populations (“subaltern studies”). In order to do so, they try to deconstruct the bias of imperial assumptions. Part of the task is to critique the imperial categories that sanctioned colonization, such as class, race, religion, and imperially defined geographical space.

A particular theme for post-colonial studies is that subject peoples, though dominated, nevertheless have agency. (There are problems here for post-modern theorists who question individual identity.) Post-colonial approaches show that subject peoples, even where they are extremely disadvantaged in their power relationships with imperial authorities, find ways to maneuver by resisting, subverting, or evading domination. Indeed, long before post-colonial studies, a principle of agency was used to explain Jewish survival through centuries of repression.

Using post-colonial approaches in Christian historiography

Post-colonial approaches have been used at the Toronto School of Theology for early Christian studies, as in a 2016 PhD thesis by Kyung-Mee Jeon, The Rhetoric of the Pious Empire and the Rhetoric of Flight from the World: a Socio-Rhetorical Reading of the Life of Melania the Younger, available here.

In Canada, post-colonial approaches have been particularly appropriate for Indigenous studies. In earlier mainstream studies, Indigenous peoples were typically just “the other” to the colonizers, without a real history. They hardly had the characteristics of the human; they were seen as what the French called sauvages. Post-colonial studies found ways to recover their history, even though in past ages they created few documents. But their past did leave other evidence in the form of oral tradition, non-documentary artifacts, and imperial records when read ‘against the grain’, that is, after the exposure and deconstruction of the colonizing mentality of their agenda, intended function, and ideology.

Brenda Macdougall’s book, referenced earlier, might be included here as a post-colonial study, since it recognizes Métis agency in a colonial context, and avoids essentializing Métis identity. A widely admired work for its original research  into first-hand sources, its command of the scholarly literature, its fresh approach, and its literary style is Susan Neylan (pictured here), The Heavens are Changing: Nineteenth-Century Protestant Missions and Tsimshian Christianity (McGill–Queen’s, 2003). Historians depending on missionaries’ reports would suppose that where missions were successful, the missionaries deserved the credit; where they floundered, the Natives were stubborn and backward. Neylan challenged that binary, reductionistic, and self-serving narrative. For instance, she discovered passionate and inventive Tsimshian catechists who adapted and inculturated the European gospel, and she showed how Tsimshian leaders could negotiate their religious space by playing Anglican, Methodist, Salvation Army, and Roman Catholic authorities off each other.

into first-hand sources, its command of the scholarly literature, its fresh approach, and its literary style is Susan Neylan (pictured here), The Heavens are Changing: Nineteenth-Century Protestant Missions and Tsimshian Christianity (McGill–Queen’s, 2003). Historians depending on missionaries’ reports would suppose that where missions were successful, the missionaries deserved the credit; where they floundered, the Natives were stubborn and backward. Neylan challenged that binary, reductionistic, and self-serving narrative. For instance, she discovered passionate and inventive Tsimshian catechists who adapted and inculturated the European gospel, and she showed how Tsimshian leaders could negotiate their religious space by playing Anglican, Methodist, Salvation Army, and Roman Catholic authorities off each other.

The value of post-colonial approaches

The post-modern turn has sometimes been seen as a revolution in historiography. But it can also be argued that post-modernism has had almost no substantial effect on how most history is actually written, even history written by people who are sympathetic to post-modern insights. The main value of post-modernity may have simply been to remind historians of the limits of knowledge, and the wisdom of being humble about their ability to access the past.