Naomi NagyLinguistics at U of T |

|

Project

1: Sociolinguistic Observation & Reporting Due: October 17, 2016 Throughout the first four weeks of the course, keep a journal recording your observations of language use and sociolinguistic variation. Your observations may serve as a source of data for your second project. A number of suggested topics are listed below, but observations relevant to any topic covered in the course are acceptable. Whenever you work with empirical data, it's important to be well-organized and use consistent formats. For this assignment, it's important to organize your observations according to the following format. Each entry should have the following three sections: a) Identifying information: Begin

each entry with an entry number, the date of observation and the relevant topic

or topics. Number all entries consecutively. b) Data: Record

the data (exactly what you observed) as objectively as possible. Do not include

judgments, opinions or comments here. Record the source of each datum: for live

observations, record the date, time, place, participants, situations, etc.. For

written media, include the standard publication information (printed articles

can be cut and pasted but must be cited properly). For electronic media (TV, radio,

internet), record the name of the station (or web site or newsgroup), the

title, the date and time of transmission, etc. N.B. Include here anything about the setting or

participants that may be relevant to understanding why the event you observed

happened the way it did. Write these facts down! c) Comments: Record your own comments, thoughts, interpretations, etc. about the data you have recorded. Why did you notice this particular event? Relate the data to things you have learned in this course. Your comments may include questions that the data raise in your mind, such as, "How do other people say or do this?" or, "Do I say things like that?" You may wish to suggest why you think the event occurred in this way, and how it might have occurred differently with other participants or with same participants in a different setting. Such observations and questions may lead to hypotheses you want to test or to subsequent observations which may ultimately answer your questions. Be ready to record observations at

all times, wherever you go, immediately, as soon as they happen. Don't wait a day, or even an hour,

because the observations will begin fading from your memory, your accuracy will

decline and important elements of the event will be lost. You should have at least six observations

to submit. Each should be about half a page long. Try to focus on just one or two of the

suggested topics. Suggested Topics for Project 1 Code-switching Bilingual

people often mix languages in the course of a single conversation

("code-switching"). Code-switching can take place within the sentence

or between sentences. Record any examples that you notice of people using more

than one language in a single conversation. Be sure to make note of what

languages are involved, and, insofar as you are able to understand those languages,

try to record exactly what was said. Also, if you yourself know more than one

language, note whether you or your family members or friends code-switch, and

make note of any examples you or they produce. In discussing such cases,

consider the following points: Why did the switches occur where they did? What

aspects of the social context permitted or encouraged such mixed use of

languages? What was the reaction of the other participants in the conversation

to the code-switching? Regional and national accents Native speakers of English show many different national and regional varieties ("dialects"). Listen for any form of English spoken by a native speaker that is different from your own. Some examples: Canadian (Newfoundland, Western Canadian, French Canadian), Australian, New Zealand, Irish, West Indian, American (New York, Southern, Californian), British (RP, Cockney, Scottish, Yorkshire). Record and comment on any distinctive features of pronunciation, grammar and vocabulary that you notice. Note your reaction to this dialect: Do you react positively or negatively? What aspects of the dialect affect your reaction the most? If you are a native speaker of another language, you might wish to report on regional or national accent variation you observe in that language instead. Foreign accents In

Toronto there are many immigrants, residents and visitors who are not native speakers of

English. How is English spoken by someone who has learned it as a second

language? Listen for any foreign accents and comment on any differences you

note in pronunciation, grammar or vocabulary. Find out what that person's

native language is. Try to determine what rule or feature of English that

person is not reproducing exactly. Note: If you speak or are learning a second

language yourself, you could compare these observations to your own speech in

that language. If you are a learner, are your mistakes similar to those made by

other people learning English as a second language? Slang and in-group words Slang refers to words and expressions that are

not generally considered part of the standard language, but are used regularly

by members of particular cultural subgroups (e.g., teenagers, computer hackers,

surfers). One reason why such groups use slang terms is to mark their

membership in the subgroup and simultaneously exclude non-members: appropriate

use and understanding of slang forms identifies someone as a fellow member,

while failure to use or respond appropriately will betray them as an outsider.

The same type of in-group use of particular words is found among people of the

same occupation, religion, etc., where the terms are generally referred to as jargon (which is generally not

stigmatized and may be more technical in nature). Collect instances of slang or

jargon that you hear around you, whether or not you are a member of the

appropriate subgroup. Record relevant information about the situation, setting,

topic and participants. Translate the form into a standard English equivalent

and try to characterize the cultural or occupational subgroup that uses this

expression. Male-female differences Collect

observations of ways in which men and women differ in their use of language.

This could include differences of vocabulary, use of polite and euphemistic

expressions, use of taboo words, use of "standard" as opposed to

"nonstandard" words or grammatical constructions, differences in

voice quality and pronunciation (e.g. pitch, breathiness, aspiration, etc.). Do

these differences in usage depend on whether the speaker is addressing someone

of the same sex or someone of the opposite sex? Are these differences the same

for all age groups? Note also any differences in the terms males and females

use to refer to other males and females (e.g. guy, girl/gal, chick,

etc.). How are these terms used to show respect or disrespect? Are they used in

comparable or reciprocal ways across the two sexes? Does the use of these terms

depend on age and social position? What words are used to refer to mixed groups

of males and females? Ethnic differences Some

features of English are often associated with speakers of particular racial or

ethnic groups, stemming either from originally foreign accents (e.g. recent

immigrant groups) or from historical segregation (e.g. African American

English). Often these features have become positive connotations as markers of

identity in the ethnic/racial group. In collecting observations of such

features, be careful to distinguish between conventional stereotypes of the way

these groups talk and what you actually observe people saying. (These are

usually not the same thing!) Carefully explore your own preconceptions about

how ethnic/racial groups different from your own speak. Social class differences Collect

observations of differences in the use of language by people of different

social classes (which may be treated as a cover term for differences in

education, occupation, status, income, etc.). Be on the lookout for usages that

strike you as nonstandard, stigmatized, 'common' or uneducated vs. those that

seem pretentious, upper-class, sophisticated, etc. Again, this could involve

vocabulary, pronunciation or grammar. Taboo words Most

languages have a number of words that are socially taboo, and in certain

circumstances even legally prohibited, referred to as "swear words"

or "dirty words". Many have central meanings related to bodily

functions (e.g. piss), body parts

(e.g. prick) or religious concepts

(e.g. goddamn), but are often used in

ways that have nothing to do with the central meaning. Such words also show

considerable gradation in the degree of tabooness. These facts mean that there

are powerful social conventions about the situations in which they may be used,

the people to whom they may be uttered and even the people who are allowed to

say them. Thus, you don't use them in formal situations (e.g. lectures) and in

the presence of certain people (e.g. mothers, priests), and certain people are

expected to use them less or not at all (e.g. women, young children). Record

your observations of the use of such terms, paying special attention to the

speaker and other people present (sex, age, class, etc.), the situation and the

meaning or intent (to express emotion, to insult). Comment in particular about

what it was about the situation which allowed these words to be used, given the

strong social taboo about the use of such words in certain situations. Note

also the reaction of those present, including yourself. Media attention to language The

mass media (newspapers, radio, TV, magazines, the worldwide web) often run

articles, stories or programs about language, including news items, interviews

with "experts", opinion columns, talk shows, letters to the editor,

etc. These usually concern the nature or quality of present-day English (what's

wrong with it, what it sounds like), the decline of standards (how corrupted

the language is becoming), new words in the language (slang, borrowings,

neologisms) and new meanings for old words. If you hear or see something like

this on TV or the radio, take notes on what is said; if you see an article in

print or on the web, photocopy it, print it or cut it out and paste it in your

journal. Comment on the following points: Do you agree or disagree with the

opinions expressed? Did the author overlook any relevant facts? Do you think

the person was fair or biased? In what way? Are the opinions expressed similar

to or different from the point of view taken in the course? In what way? Style-shifting All

speakers adapt their way of speaking to different audiences, topics and

settings. They can speak formally in public, professional or official contexts

(e.g. classrooms, business meetings, public speeches), or they can be informal

in private and personal contexts. They can show politeness and deference to

social superiors (e.g. teachers, employers) or assert authority over social

inferiors (e.g. employees, children). They can demonstrate familiarity or

intimacy (e.g. friends, family) or distance (e.g. strangers). This dimension of

variation in language use is often described as "speech style" and

when a speaker changes from one style to another, it is referred to as

"style-shifting". Make note of any examples of style-shifting that

you encounter. This may be especially noticeable in contexts where speakers are

relating to different audiences in rapid succession. For example, in a

classroom setting, students may use one (formal) style to speak to the

professor or to contribute to a classroom discussion, and a different

(informal) style to carry on a private conversation with a friend in the class.

At home, you may speak more formally to your parents than to your siblings. For

observations of style-shifting, be sure to make note of the social relationship

between the speaker and the addressee(s). Also, try to characterize the nature

of the speech style used in each setting or with each audience in terms of

(in)formality, familiarity/distance and politeness. A Small Study of Sociolinguistic Variation Due: November 30, 2016 (Week 12, hard copy due in tutorial) In

this assignment, working individually or in groups of up to 3, you will study

the use of a sociolinguistic variable. You may collect data by means of

participant observation (i.e. by noting relevant examples of the feature you

are studying whenever they are used in your presence) or use existing data as specified below. You may choose any one

of the suggested topics to work on, or suggest a variable of

your own after consulting with the

professor. You may use observations from Project 1.

Step 2. Data Collection

Over

a period of a week, each person should collect a minimum of 25 tokens (occurrences) of the variable. A good practice

is to keep a notepad with you at all times, so that whenever you hear somebody

using the variable, you can write down which variant they used, as well as

other relevant information about the situation: • sex of the speaker: -

try

to obtain roughly equal numbers of tokens from males and females • sex of addressee/hearer (including

yourself) • familiarity of speaker and

addressee/hearer -

distinguish

‘familiar’ interactions (friends and family members) from ‘less familiar’

interactions (acquaintances or those in a formal relationship, such as

student/teacher or employee/employer) -

try

to obtain roughly equal numbers of tokens from familiar and unfamiliar

interactions -

make

note of other features of the context that would make the interaction more or

less formal, such as the topic of conversation and the setting • channel of communication: -

make

note of whether each token occurred over the telephone or internet vs.

face-to-face, through speech vs. writing, through participant observation vs.

questionnaire, etc.

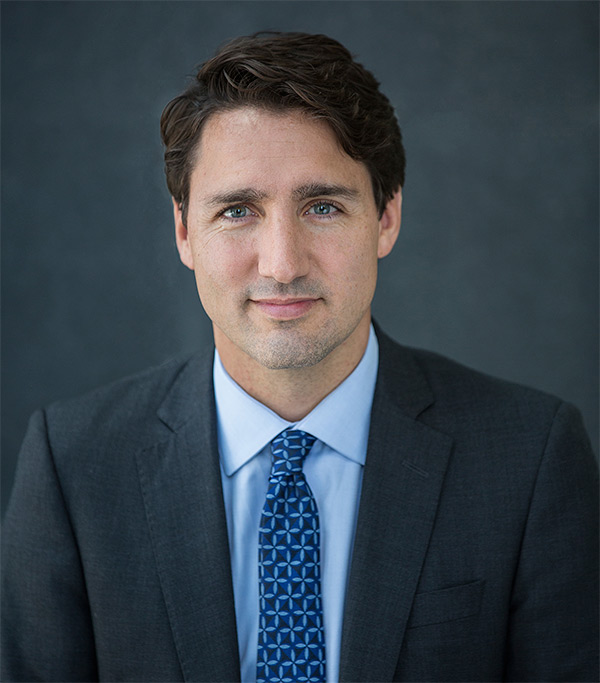

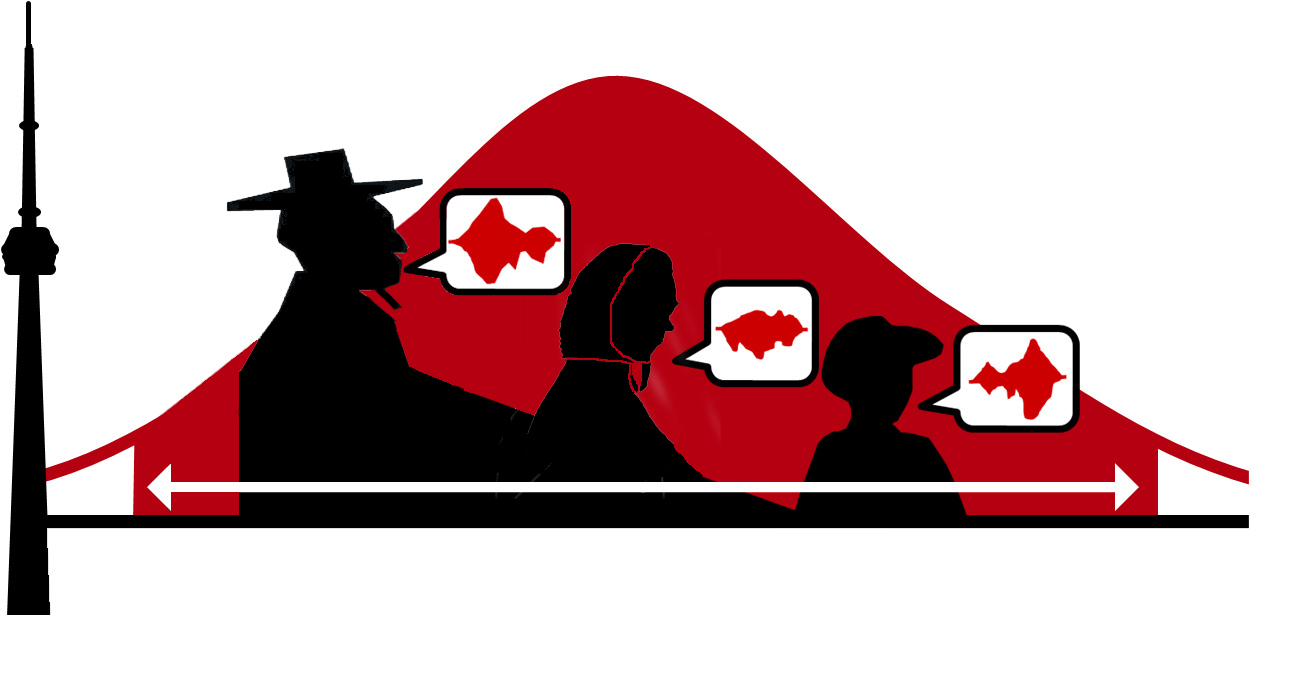

Although Prime Minister Justin Trudeau has gotten a lot of media attention in his first year in office, sociolinguists have yet to publish any analysis of his speech, as far as I know. Many questions come to mind:

To answer one of these questions (or a similar one that the professor has approved, you need to find recorded and/or transcribed speech. This choice depends on what kind of variation you want to examine. You will need at least 3 minutes of speech to examine. Many samples exist online.

If

you/your group is able to work with spoken recordings of one of the languages

in the

(Heritage Language Variation and Change project), select a minimum of three

speakers that have been recorded and transcribed. Find at least 25 tokens

(occurrences) of the variable in each recording. A good practice is to create

additional tiers in the ELAN .eaf file and mark and code the tokens there. In

one tier, note which variant they used. In additional daughter tiers, note the other

relevant information about the situation (see list in Option 1). The tokens and

tiers can then be exported to a spreadsheet for easy analysis.

Step 3. Data analysis Summarize

your results in the form of tables, showing what proportion of tokens of each

variant you encountered (e.g. formal vs. informal greetings, -ing vs. -in’) were uttered by males as opposed to females, addressed to

people with whom the speaker was familiar vs. unfamiliar, were spoken over the

telephone vs. face-to-face, etc. Consider carefully how your different variants

might best be grouped together. (e.g., Are some of the greetings more formal

and others more familiar? Are some taboo words extremely taboo and others only

mildly so?) If you identify groupings like this in the data, use them in your

tables. Wherever possible, express your results as percentages, calculating

proportions within each category. For example, what proportion of familiar

greetings were used by men vs. by women? Step 4. Research Report Write

a report (4-5 pages) describing your study. It should include an informative

title and the following short sections in order: i)

Introduction State

the variable, what the variants were and why this was interesting or what

general issues it related to (i.e. your goals and hypotheses). ii)

Methodology Describe

how you collected, coded and analyzed the data. iii)

Results Organize

your research findings into tables broken down by social categories (sex,

familiarity, etc.). iv)

Discussion Discuss

your results and their implications. Think about questions that have been

addressed in the class. Make explicit reference to at least two of the assigned

articles, as well as relevant concepts from the textbook. Address questions

such as the following: Do men and women show different preferences for the

various greetings or leavetakings, or pronunciations of -ing? Do men use more strong taboo words than women? Do women use

more information-seeking tags than men do? Do speakers use different greetings

or leavetakings over the telephone than in person? Do people code-switch more

often with people they know well as opposed to those they have limited

acquaintance with? Does pronunciation of -ing

vary with the formality or familiarity of the situation? v)

Conclusion Try

to draw general conclusions about your results. Why did the results come out

the way they did? Why do (or don’t) women and men differ in the use of these

features? Why do speakers use different forms in different interactions? Where

possible, try to identify future areas for possible research. vi)

Bibliography List

all published references, including websites, that you consulted. Cite them

appropriately within your paper. There are resources in the course Blackboard

site for help on citation and reference practices. Evaluation Evaluation

of the assignment will be based on the following considerations: Structure: -

organization;

clarity; spelling and presentation (use a

spell-checker!) Content: -

how

well have you defined the variable context (i.e. where does the speaker have a

choice between variants?)? -

how

well have you discussed your methods of data collection? -

how

well have you discussed the details of your quantitative analysis (your social

factors, your calculations)? -

how

well have you made use of tables and graphs? -

how

well have you synthesized and interpreted your results? -

how

well have you made connections between your results and the course materials

(textbook, readings, lectures)? If you work in a group, you

will submit one co-authored paper.

Be sure that the title and all authors' names are listed at the top of page 1. You do not need to create a separate title page. You are encouraged to print two-sided. Greetings and/or

Leavetakings When

people encounter one another after a period of not being in each other's

presence, they normally use some kind of greeting (e.g. hi, hello, good morning); similarly, when people

terminate an encounter and expect not to be in each other's presence for some

time, they ordinarily mark this with a leavetaking (e.g. goodbye, see you).

Greetings and leavetakings mark different social relationships between speaker

and hearer. Make note of all greetings and/or leavetakings addressed to you or

to others in your presence and try to characterize the social significance of

each (i.e. which ones are more or less formal, express solidarity or

familiarity, etc.). You may want to divide your greetings/leavetakings into two

variants: ‘formal’ and ‘informal’. Try to characterize any preferences that

different speakers or groups of speakers tend to have (e.g. Do men use informal

greetings more than women?) and whether usage is affected by the channel of

communication (telephone vs. face-to-face). Taboo Words Taboo

words (commonly referred to as "swear words", "curse words"

or "dirty words") are subject to strong social conventions about

their usage. Note all instances of such words that are used in your presence.

You may want to divide the different taboo words into two variants: ‘mild’ and

‘strong’. Try to characterize

whether men and women use taboo words differently and whether people are more

or less likely to use them in the presence of people they know well as opposed

to those they are less familiar with, or in the presence of women as opposed to

men. Tag Questions Robin

Lakoff (1975) has suggested that women use tag questions more than men because

tags signify a desire for confirmation or approval and therefore relative

powerlessness or lack of self-confidence (e.g. It’s a nice day, isn’t it? is supposedly less assertive than It's a nice day.). Collect observations

of male and female speakers using tag questions. You may want to divide the tag

questions into two variants: ‘polite/deferential’ and ‘seeking confirmation’.

Note especially when the tags are used differently from the way you would use

them. In your analysis, discuss whether your data confirm Lakoff’s hypothesis

or not; i.e. do men and women use these forms with different frequency or

different significance? -in/ing The

-ing suffix in English (e.g. building, running, opening) is

sometimes pronounced as 'ing' and sometimes as 'in' (known as "dropping

the 'g'"). Since the social evaluation of each pronunciation is different,

speakers often vary their usage according to formality, and speakers of

different social backgrounds may show different overall rates of usage. Data

collection for this feature requires close attention to phonetic detail:

practice listening to the pronunciation of -ing

words in conversation before you begin collecting data. (When you begin writing

down your observations, they will probably occur so frequently that you will be

able to collect enough data to work with in a day!) Therefore, try to observe

people from a range of social backgrounds. In

addition to social variation, this variable is also subject to an interesting

linguistic constraint. To examine this, you should classify each example you

observe as to whether it was used as a noun (e.g. the building across the street, running is fun) or a verb (e.g. we're building a house, he's running to work). Your analysis

should address the following questions: Is there a sex difference in the usage

of the two pronunciations? Do speakers shift towards increased use of one of

the pronunciations in more formal situations (e.g. lectures) as opposed to

informal ones (e.g. casual conversation)? Is there any such shifting depending

on the sex of the addressee or the channel of communication? |