Please note that reproduction of any of the contents of this page is prohibited.

• Tagliamonte and Roeder 2009 Tagliamonte and Roeder 2009 (© 2009 Sali A. Tagliamonte) 2009. Sali A. Tagliamonte and Rebecca V. Roeder. Variation in the English definite article: Socio-historical linguistic in t'speech community. Journal of Sociolinguistics, 13(4), 435-471. This paper provides a sociolinguistic analysis of variation in the English definite article, a.k.a. definite article reduction (DAR), in the city of York, northeast Yorkshire, England. Embedding the analysis in historical, dialectological and contemporary studies of this phenomenon, the findings uncover a rich system of variability between the standard forms as well as reduced and zero variants. These are involved in a system of multicausal constraints, phonological, grammatical, and discourse-pragmatic that are consistent across the speech community. However, the reduced variants are not derivative of each other, but reflect contrasting functions in the system. Interestingly, the reduced variants are accelerating in use among the young men, suggesting that DAR is being recycled as an identitymarker of the local vernacular. This change is put in sociohistorical context by an appeal to the recently developing interest and evolving prestige of Northern Englishes more generally. Audio examples of definite article reduction in York English (? = reversed glottal stop) Male speaker born in 1906 (91 years old in 1997) The main thing is be happy. And if I get a bit miserable with miself, I go t ? top ? garden and talk to mi tomatoes. Male speaker born in 1905 (91 years old in 1996) T' only thing - only way you'd find ? well would be to follow ? pipe from where ? pump was. Female speaker born in 1959 (38 years old in 1997) We both went t ? chip shop. Next thing I know, these fellas are picking me up off the floor (laughs). I remember handin' t' ten pound note over and that was it...gone onto ? concrete floor. Female speaker born in 1959 (38 years old in 1997)

These professional ones that fish on ? lakes now all ? time. You ever been up there t ? lakes? [To the Lake District? Yeah. I used to go up there quite a bit with my parents.] Tagliamonte and Molfenter 2007 (© 2007 Sali A. Tagliamonte) 2007. Sali A. Tagliamonte and Sonja Molfenter. How'd you get that accent? Acquiring a second dialect of the same language. Language in Society, 36(5), 649-675. This article presents a case study of second dialect acquisition by three children over six years as they shift from Canadian to British English. Informed by Chambers's principles of second dialect acquisition, the analysis focuses on a frequent and socially embedded linguistic feature, T-voicing (e.g., pudding versus putting). An extensive corpus and quantitative methods permit tracking the shift to British English as it is happening. Although all of the children eventually sound local, the acquisition process is complex. Frequency of British variants rises incrementally, lagging behind the acquisition of variable constraints, which are in turn ordered by type. Internal patterns are acquired early, while social correlates lag behind. Acceleration of second dialect variants occurs at well-defined sociocultural milestones, particularly entering the school system. Successful second dialect acquisition is a direct consequence of sustained access to and integration with the local speech community. Audio examples of Tara acquiring British English:

Sali: But she can't do anything with it, sweetheart. Where are you going, Shay? Tara: Thank you, Mum. It's making me draw much better [d]. Look at my girls. Mine are prettier [d] than Shaman's.

Tara: Is that a beautiful [d] thing? We'll do the inside of that [?] after. So let's do teamwork. I'll do this, and then you do that.

Sali: This is March the ninth, nineteen ninety seven.

Tara: Mommy! That will be beautiful [t] in the end, won't it?

Tara: Butter [t], melted butter [t]. Melted butter [t].

Tara: Look at what [?] I'm making, Mum, clover leaves.

Tara: Girls are better [d] than boys I think. Mm. Mommy, you know, girls- guess what? Guess what, boys at my school think girls are sort [d] of rubbish.

Tara: What was your favourite thing when you were little [?] ?

Tara: Starting [t] to get juicy. Freya, that's- Freya just took a bite [?] out [?] of this. Tara: Daddy said he forgot [?] about [?] it [?] and he didn't.

Tara: Have we got [?] eggs?

Tara: Okay, Mommy, have you got [t] a three? Ha! Tara: Do you know what [d] it [?] is now?

Tara: Mommy, I'm right.

Tara: Mommy, there's the potato [t].

Tara: Have you got [d] a joker?

Tara: Yeah, she's gonna get [?] out [?] of it. She's got really sick and tired of it. 'Cause she can't do anything, she can just walk around in it. But, her leg's getting [?] better [?]. 'Cause you c-- ‘Cause when I went down to Joanna's sleepover you could actually see the bump in her cast where the bone poked out [?] of her skin. Findings from the Toronto English Project (© 2006 Sali A. Tagliamonte)

2005. Alexandra D'Arcy. Like: Syntax and development. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Toronto.

The use of quotatives in Toronto Quotatives are words that people use to quote what people say. Here are some examples of quotatives in Toronto English:

He's like, "Yeah."

This figure shows how often each of several quotatives is used in Toronto by people of different ages:

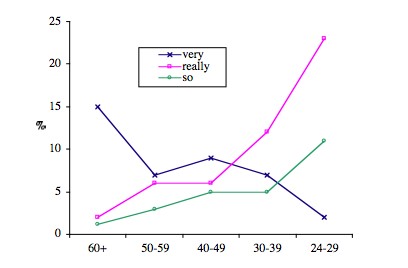

The use of intensifiers in Toronto Intensifiers are adverbs that boost or maximize the meaning of an adjective, as in the examples below:

If he's really dull, but he's like, so hot...

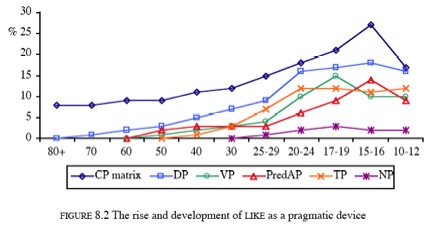

This figure shows how often each of the main intensifiers in Toronto is used by people of different ages: The use of like in Toronto (D'Arcy 2005) A lot of people think that teenagers use like frequently. But how frequently? Can like really go anywhere? Here are some examples of like in Toronto: 18-year-old female speaker: I love Carrie. Like, Carrie's like a little like out-of-it, but like she's the funniest, like she's a space-cadet. Anyways, so she's like taking shots, she's like talking away to me, and she's like, "What's wrong with you?" 75-year-old female speaker: Well, you just cut out like a girl figure and a boy figure and then you'd cut out like a dress or a skirt or a coat, and like you'd colour it.

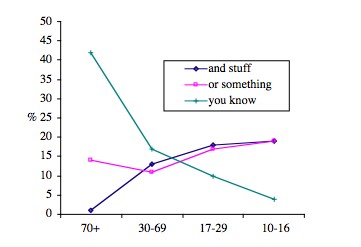

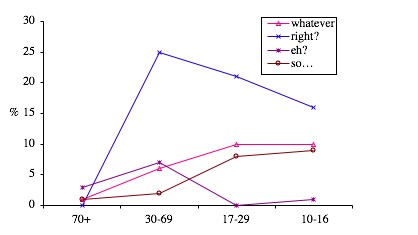

In her 2005 Ph.D. dissertation, Alexandra D'Arcy analyzed the use of like acording to speaker age in Toronto. One of her main findings is that like is used systematically and is gradually evolving. This figure shows the linguistic contexts in which like appears. The use of tags in Toronto Tags are forms which often end sentences. Although eh has become an icon of Canadian English, there are actually dozens of other ways Canadians end their sentences, as in the examples below:

It's about like animals and stuff, right?

And stuff is used most often by younger people, while you know is preferred by older speakers. Or something, on the other hand, is relatively stable across age groups:

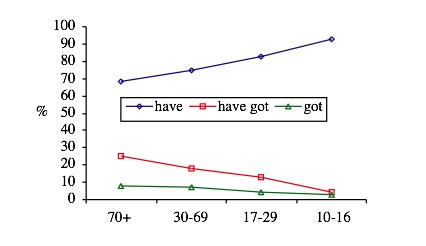

The use of have/has in Toronto to describe possessions and states-of-affairs Torontonians can say 'I have a cat' or 'I've got a cat'. Notice the different uses in these examples:

It has a huge diving platform, diving tower and an Olympic size pool, and we've got hundreds of thousands of people going into that pool.

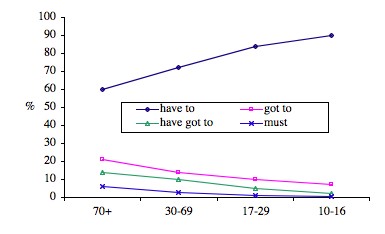

Do people choose between have, got, and have got randomly? Or is there a pattern? This figure shows how often each form is used in Toronto by people of different ages: The use of have to/has to to express obligation or necessity in Toronto Deontic modality is the expression of obligation or necessity. There are many ways to express obligation or necessity in Toronto English:

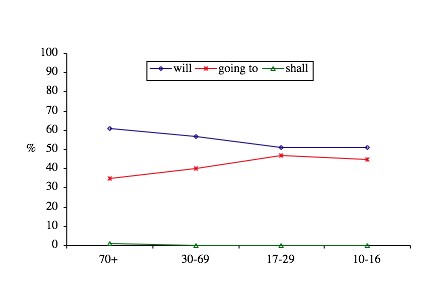

I must admit I think I was a little bit of a city snob. This figure shows how often each form is used by speakers of different ages: The use of the 'going to' future in Toronto There are two main forms used to express the future in Toronto English: will and going to.

Music's gonna evolve and change, so language will evolve and change too. This figure shows the distribution of these forms in Toronto by people of different ages:

|